Another book hits the wall

Maybe this substack should be titled 'Books I do not finish'.

This time, it was The Boleyns by Amanda Harvey Purse. I was deceived by the cover blurb quotes from Tracy Borman and Owen Emmerson - two historians who have done some solid research. To reconcile my disappointment or the fact that I was naïve enough to fall for the cover blurb quotes, I choose to believe that neither Borman nor Emmerson actually read the book.

I had to buy it. It’s about the Boleyns, and my doctoral work is about the Boleyn kinship network.

My suspicions about the book were aroused when I couldn’t find a bibliography. There are endnotes for each chapter. That’s good. This indicates that there is some proof or at least evidence supporting the assertions that the author is making. But there’s no listing of all the sources those end notes name. The first step in any serious research project is to mine the bibliographies of books. This leads you down multiple rabbit warrens of information, following the byzantine paths of the researchers who went before you. Eventually, you reach the bottom, and if you are an historian, that bottom is the manuscript archives.

The conceit of The Boleyns is that there was more to the Boleyn family than their most famous daughter, Anne and that they are still with us. The subtitle is ‘From the Tudors to the Windsors’. King Charles III is a descendant of Mary Boleyn, Anne’s sister. Thanks to Phillipa Gregory, Mary is now known in popular culture as ‘The Other Boleyn Girl’. I had to buy the book.

Predictably, the book starts with a short genealogical tree of the early Boleyns ending with Queen Elizabeth I, daughter of Anne Boleyn. The first chapter dips into great-great-grandfather Geoffrey Boleyn and explores some cadet branches of the early family but quickly fast forwards to Anne Boleyn’s imprisonment in 1536, awaiting execution ordered by her husband Henry VIII. In this still-the-first chapter, Anne’s execution is used to attach relevance to a minor character, Elizabeth Wood Boleyn.

According to Purse, Henry VIII chose people to attend Anne from her family who “did not like her, making Anne feel alone at the end”. Really? Being thrown in prison, prevented from seeing her daughter, having every word and action reported by attendants to the king, and waiting for an executioner swordsman from France to cross the channel wouldn’t make one feel alone? I hardly think we need to pile on here to ramp up the drama. Plus, there’s no evidence that her family disliked her.

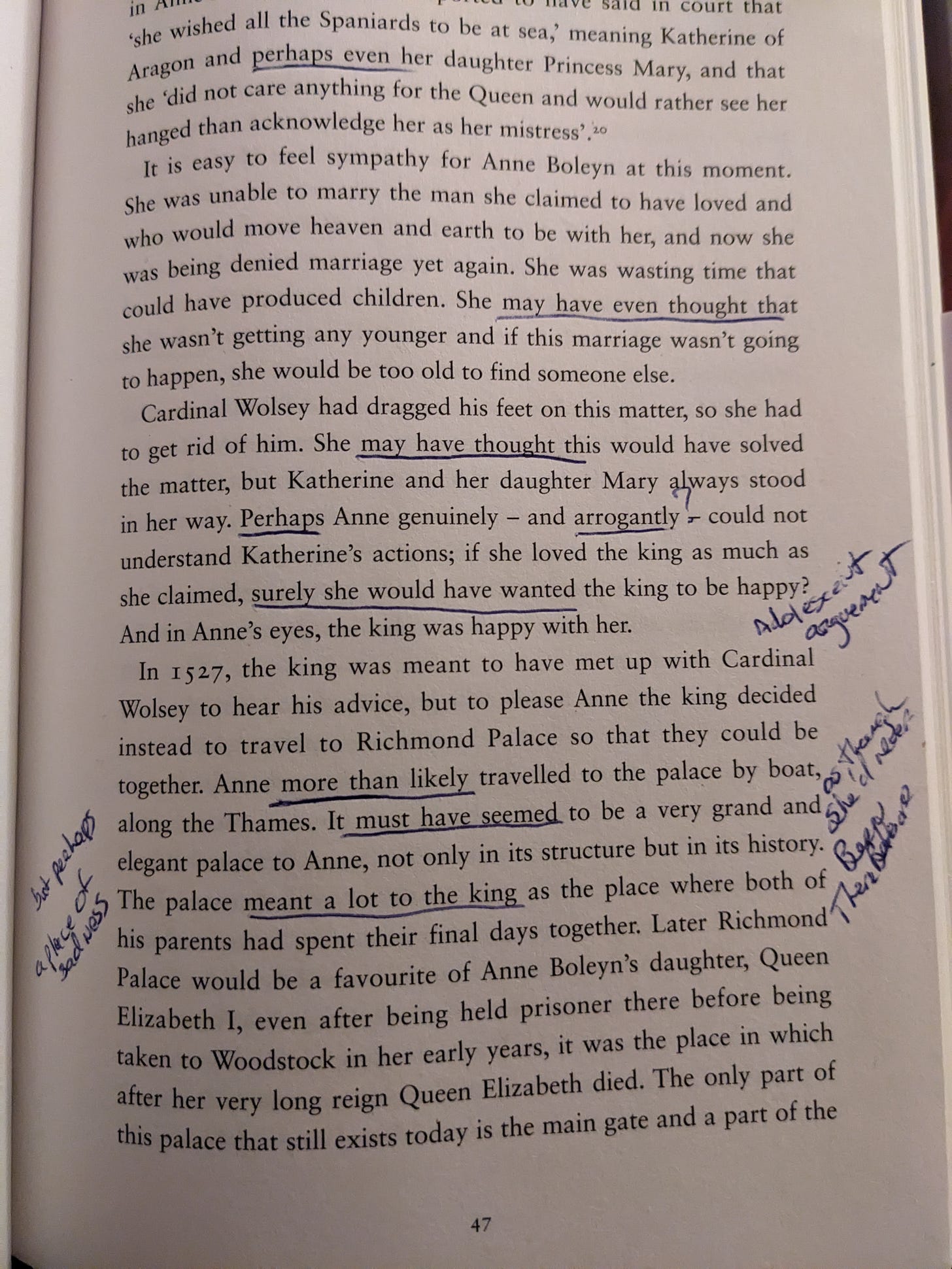

Predictably, there are several hypotheticals woven throughout the text. I suspect that without them, the text would be lying on the ground, an incoherent pile of nouns and verbs. In this book, the hypotheticals are the narrative. Apparently, Elizabeth Wood Boleyn “could have been the ‘Lady Boleyn’ who attended Anne in the Tower. She “could have been one of the ladies that followed Anne” to the scaffold. “She may have been one of those who helped undress Anne after she had been beheaded,” and “she may have even helped to carry the wooden chest” to the chapel in the Tower where we presume Anne was buried.

All these conditional phrases are the way authors imagine the past. Every time you read these phrases, know that the next few sentences are made up. Fiction.

By page 29, I had begun underlining in ink - another sure sign of my growing irritation for the text (the archives trained me to use pencil only). All the conditional phrases had me writing snarky comments in the margins like ‘how do you know?’ ‘totally made up’ and ‘are you kidding?’.

Then we get to simple math and the author’s search for controversy in the historical record. She relays that “On 25 January 1533, the king apparently married Anne Boleyn.” In an attempt to cast a shadow on this date - which by the way, is considered the ‘formal’ wedding date - she claims that the king, desperate for a legitimate male child, would never have allowed a child to be conceived out of wedlock. The kicker is that child, Elizabeth, was born nine months later, in September. No controversy. Perfectly legitimate. (Most historians accept that there was an earlier private wedding on 14 November 1532 and that this marked the start of the couple’s conjugal relations.)

This glancing understanding of early modern marriage, legitimacy, pregnancy, and the Tudor court generated even more inky comments, blots, and scratches culminating in a much-needed vodka.

To prevent, Dear Reader, your complete, utter, and inevitable boredom bound to happen if I nerd out on all the things wrong with the next couple of chapters, I will skip to the first time I threw the book across the room. OK - just one: Purse says that the plaque in Westminster Abbey claims Henry Carey, Baron Hunsdon died in 1591. WRONG! He died in 1596. Says so right on the monument, which is the biggest in the Abbey.

In the chapter on Lettice Knollys Devereux Dudley Blount, Countess of Essex and Leicester, granddaughter of Mary Boleyn, the author introduces the famous Cor Rotto letter. This letter was written by the then Princess Elizabeth expressing support and sorrow at the imminent departure of her good friend ‘Lady Knollys’ in 1553. If Purse had used the same logic she employed earlier to puzzle out an identity for ‘Lady Boleyn,’ she would not have made the egregious error of claiming this letter was addressed to Lettice. In 1553, Lettice was ten years old. At best, she would have been ‘mistress’.

Alternately, she could have read any of the dozens of works on the Boleyns and the hundreds of works on Queen Elizabeth I to know that this letter was addressed to Katherine Carey Knollys, Lady Knollys, Lettice’s mother.

Side note: I’ve contacted the British Library, where the original is held. They are trying to get the digital image but are currently recovering from a cyber attack that shut down their website.

Purse claims that Lettice traveled to London in 1565 to attend Henry Devereux's wedding to Margaret Cave. No again. This would have had Lettice attend the wedding of a member of her husband’s family that, according to the genealogy, does not exist. Instead, the groom was Lettice’s own brother Henry Knollys, and it was the wedding of the year. The queen had to negotiate a matter of precedence amongst the ambassadors attending. There was a tournament and so much celebration that it was used as cover for Mary Grey, sister to the Nine Days Queen Jane Grey, to elope with Thomas Keys, a sergeant porter - a scandal for another time.

The pervasive nature of the errors makes me wonder about the ‘fast fashion’ model to which publishing has fallen prey. Colleagues have advised me to write the publisher to point out errors in case the tome reaches a second edition. For the Tudor fandom, I certainly hope it does not. In fast fashion and fast publishing, there is little incentive to correct faults in design or craft as it is presumed styles will move on in a few months. Unfortunately, I doubt the ardor for all things Tudor will fade before the next publishing cycle.

There’s a corner of my mind whispering that those who live in glass houses should not throw stones at people who have actually managed to get a full monograph published. Something I have not done within the history genre.

I prefer to focus on the object lesson this book provides, and like Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth (1998), despite the accusation of treason to the historical profession that I have made against this book, I will choose to keep it on my shelf instead of burning it at the stake ‘To remind me of how close I came to danger’.

Tell true stories. They take time.